1 Passacaglia

Luigi Rossi

2 Elena invecchiata

Marco Marazzoli

3 Spargete sospiri

Luigi Rossi

4 Lamento d’Artemisia

Marco Marazzoli

5 Pianto della Maddalena

Luigi Rossi

6 Perché dolce Bambino

Marc’Antonio Pasqualini

7 Piangete occhi, piangete

Domenico Mazzocchi

8 Peccantum me quotidie

Luigi Rossi

9 Conclusion of Oratorio

Luigi Rossi

per la Settimana Santa

ERIN HEADLEY - director

NADINE BALBEISI soprano

THEODORA BAKA mezzo-soprano

Paulina van Laarhoven and Annalisa Pappano - viola da gamba

Nora Roll - viola da gamba and Erin Headley - viola da gamba, lirone

Kristian Bezuidenhout - harpsichord

Siobhán Armstrong - arpa doppia

Elizabeth Kenny and Andrew Maginley – chitarrone

NI6152

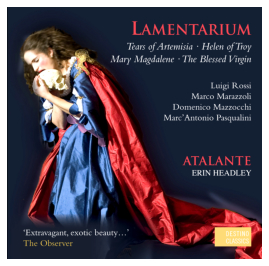

Eternal lamenting, extravagant repenting, religious ecstasy…passionate, sensual, macabre

and erotic narratives from 17th-century Rome

RELIQUIE DI ROMA I: Lamentarium

ATALANTE

REVIEWS

Breathtaking performances of delicious music

Marc Rochester Gramophone Magazine

OUTSTANDING Release April 2012 International Record Review

Music of the highest invention and emotional sophistication read more

Andrew O'Connor International Record Review

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recording Of The Year 2011

One of the best recordings I have heard all year read more

Johan van Veen MusicWeb International

…will surely come to be regarded as a something of a milestone read more

Iain Fenlon Early Music

The kaleidoscopic continuo expertly led here by the group’s director, Erin

Headley, contribute enormously to the success of this album. read more

Gaëtan Naulleau Diapason

If your head has ever been turned or your heart pierced by Monteverdi’s more

famous laments, you’ll probably love this. read more

Michael Dervan Irish Times

I can’t believe that Lamentarium from Atalante director Erin Headley will not

be in my top ten recordings of the year. read more

Tim Thurston RTE Lyric FM Ireland

Stirring renditions by soprano Nadine Balbeisi and mezzo Theodora Baka of

little-performed works read more

Andy Gill The Independent

Breathtaking performances of delicious music associated with Pope Urban VIII

It takes a very special skill to be able to convey in a single disc the range of moods – passionate, sensual, macabre and

erotic – that these four composers evoke in their music, but guided by the graceful Erin Headley, the musicians of

Atalante achieve it with spectacular success. While an atmosphere of retrospection hangs around much of the music,

reaching its delicious apogee in the spine-tinglingly anguished opening of Rossi's reflections on the plight of Mary

Magdalene as she lay at the foot of the cross, Pender non prima vide sopra vil tronco, there are also moments of extreme

sensuality and high drama.

Nadine Balbeisi has a voice of extraordinary purity, flawless in her intonation, perfectly balanced across her entire range

and always singing with effortless composure. As the grief-stricken Mary Magdalene or as the angelic observer of the

birth of Christ in Pasqualini’s lovely miniature, she is superbly sensitive. Theodora Baka, on the other hand, brings

considerable warmth and potent dramatic presence, and is utterly convincing as Helen of Troy in Marazzoli’s Cadute erano

al fine. In the duets, the two voices coalesce so completely that the effect is quite unnerving.

Described as Vol 1, so hopefully more are to follow, the disc explores the work of those composers associated with the

Barberinis (Pope Urban VIII and his family) who encouraged a culture of ‘extravagant repentance, lamenting and

religious ecstasy’. These elements are perfectly portrayed in these breathtaking performances.

Marc Rochester Gramophone Magazine

OUTSTANDING Release April 2012 International Record Review

Music of the highest invention and emotional sophistication. The rich accompaniment by Atalante, not least the

unique sound of the lirone, surrounds the voices like luxurious Baroque embroidery.

This is the debut recording by the ensemble called Atalante, which was formed in 2007 by Erin Headley as a vehicle for

the instrument she has rediscovered and championed: the lirone. This is a fretted string instrument with between 9 and 14

(or, according to some, 16 or even 20) strings made from gut. It is about the size of a cello but has a flat bridge which

allows for the playing of chords, using between three and five strings. The lirone is held between the legs and played with

the bow held from underneath as with the viola da gamba. According to Headley, the instrument was invented in 1505 by

a friend and pupil of Leonardo da Vinci named Atalante Migliorotti and the ensemble is named in his honour. The golden

age of the lirone was the late Renaissance and Early Baroque. Its rich, sonorous, sometimes shimmering timbre was much

favoured in continuo groups accompanying arias and recitatives in operas, cantatas and oratorios. Such rich continuo

groups typically also featured a double harp, guitars, lutes or chitarrones, harpsichord and sometimes several viols, which

instrumentation is essentially reproduced in Headley's ensemble. It is interesting to see the harpsichordist in the ensemble

is the well-known Fortepianist Kristian Bezuidenhout.

Laments and other tragic scenes were the especial preserve of the lirone. Monteverdi's Lamento d'Arianna of 1608 created

this genre, which enthralled composers and audiences in Italy and beyond for most of the seventeenth century. Many

operas and oratorios contained lengthy laments, which often took up an entire scene. Chamber cantatas including or

entirely comprising laments were also very popular. Female characters drawn from mythology or religion were much

favoured, but not exclusively so. They were subtly sensual works, often tinged with a Bernini-like eroticism. Sometimes

laments were composed on topics drawn from recent history or almost current events. Perhaps the oddest and most

provocative was Barbara Strozzi's Lamento del Marchese Cinq-Mars, which dealt with the fall and execution in 1642 of King

Louis XIII’s proud and petulant young lover Henri d'Effiat, Marquis de Cinq-Mars.

There is nothing so scandalous or politically charged in the laments Headley has chosen for this disc, with the Virgin

Mary, Artemisia, Mary Magdalene and the aged Helen of Troy (’Elena invecchiata’) among the mourning characters

depicted. There is also a lament on the death of Christ, Piangete occhi, piangete by Domenico Mazzocchi, where the

weeping protagonist is an anonymous Christian believer. The very learned booklet essay, presumably by Headley, points

out that, at least in public performance and particularly in Rome, these laments ‒ regardless of whether they concerned

male or female characters ‒ were commonly sung by castrati. However, women singers certainly performed them at

private musical gatherings hosted by the Roman aristocracy ‒ both social and ecclesiastical.

The composers featured in this programme were among the finest and most celebrated of the Roman school of the early

and mid-seventeenth century. The laments are substantial pieces (Luigi Rossi's Pender non prima vide sopra vil tronco ‒

‘Tears of Mary Magdalene’ lasting 19 minutes), generally constructed with a mixture of highly expressive recitative, arioso

passages and occasional gentle ostinatos. They are, without exception, music of the highest invention and emotional

sophistication. The rich accompaniment by Atalante, not least the unique sound of the lirone, surrounds the voices like

luxurious Baroque embroidery. This is consistent with the booklet photographs of the two singers and musicians in

period costume and staging from semi-theatrical productions of this programme. It is a shame that apparently no DVD

(or better, Blu-ray) recording has been issued.

The two singers, both strikingly attractive, are the Jordanian-American soprano Nadine Balbeisi and the Greek mezzo-

soprano Theodora Baka. I was initially a little hesitant about Baka's voice, which has just a touch too much vibrato for my

purist tastes; however, after a while, her warmth of timbre and profoundly moving singing won me over. No such period

of adjustment was needed in the case of Balbeisi, since I was already a strong admirer of her from her work with the duo

ensemble Cantar alla Viola. Her highly expressive and utterly pure voice is the perfect instrument for this repertory. Her

performances on this disc are, in a word, ravishing.

There are three brief instrumental interludes, two of which are transcriptions of vocal works, which Atalante plays with

quiet intensity and incomparable grace. It is rather a relief to hear early seventeenth-century music played, for once,

without percussion. Both vocal and instrumental works are given a wonderfully vivid recorded sound.

Without wishing to sound snobbish, this is not a programme for the casual listener. It features music written for

connoisseurs. Their successors today will find this in every way an outstanding recording.

Andrew O’Connor International Record Review April 2012

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recording Of The Year 2011

The repertoire reflects the sense of experiment and invention which is a feature of Italian music of the early 17th-century.

The performances of the recently-founded ensemble of Erin Headley are just as exciting as the music. The two singers,

Nadine Balbeisi and Theodora Baka, deliver impressive performances.

One of the best recordings I have heard all year.

As its title indicates this disc is entirely devoted to laments. This was a popular genre in the 17th century. Some laments

belong to the most famous pieces, like the Lamento d’Arianna by Monteverdi - the only surviving fragment from his lost

opera. Then there’s the lament of Dido at the end of Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas. Various terms were used to describe

them: lamento, pianto or lacrime (‘tears’). This disc could also bear the title ‘Piangete occhi, piangete’ - Weep, eyes, weep! -

because that phrase returns in various pieces.

All these compositions were written by composers who worked in Rome, and in particular in the service of members of

the Barberini family, one of the most wealthy in Italy. They were a Tuscan dynasty of wool merchants who also played a

role in the church. When Maffeo Barberini was elected pope in 1623 - under the name of Urban VIII - he made two of his

nephews cardinal, a third became Prince of Palestrina and commander of the Papal army. Together they acted as patrons

of the arts in Rome, surrounding themselves with some of the best poets, artists and musicians. Among the most celebated

musician-composers in their service were Girolamo Frescobaldi, the chitarrone virtuoso Johann Hieronymus Kapsberger

and Stefano Landi, castrato and player of the harp and the guitar. The main composers on this disc, Luigi Rossi and Marco

Marazzoli, were also singers and harpists.

Marazzoli was at the service of Cardinal Antonio Barberini. The largest part of his oeuvre - oratorios, operas and cantatas -

was written for the Barberinis. The same Cardinal was also the patron of Luigi Rossi, one of Rome’s main composers. He

has become especially famous for his opera Orfeo which was written for performance at the French court. This was at the

request of Cardinal Jules Mazarin, who was of Italian birth and belonged to the Barberini network. The disc opens with a

Passacaglia, an independent instrumental piece which may have been written while Rossi was in France.

The laments were not just written for musical entertainment. They also had a spiritual meaning, even those with secular

content. Despite their love of splendour and their wish to display affluence, the Barberinis were also staunch supporters of

the Counter-Reformation. And music was an important instrument by which to spread the ideals of this movement. The

fact that worldly subjects were part of it only confirms that in this time there was no strict division between sacred and

secular. A good example is the second item, Marazzoli's Lamento d’Elena invecchiata, the lament of the aged Helen,

meaning Helen of Troy. It begins with a passage for a testo, a narrator. Oratorios, for instance those of Giacomo Carissimi

(another Roman composer) often also had a role for a testo, telling parts of the story and introducing the characters - very

much like the Evangelist in Bach’s Passions. This lament is the musical counterpart of paintings with a vanitas subject

which were also used for the promotion of ethical values. In this case the moral lesson is the vanity of beauty. The narrator

concludes: ‘And so she [Helen] showed us through the fragile mirror, how fragile is a beautiful face’.

Another secular piece is the Lamento d'Artemisia, also by Marazzoli. The title figure was Artemisia II, who after the death

of her husband Mausolus ruled Caria from 353 to 351 B.C. She laments the death of Mausolus, and several historical

figures are mentioned. This is, according to the liner-notes, one of the reasons this repertoire is not often performed. There

are many references to figures and situations which are not familiar to modern audiences. That was different at the time

this music was written, as the audiences consisted of aristocrats and clergymen who were very well educated.

The longest piece is of a sacred nature. Luigi Rossi’s Pianto della Maddalena is about Mary Magdalene who threw herself at

the feet of the cross and ‘in sobs and sighs and with these bitter notes, gave voice to her sufferings’. Here we not only find

sadness and grief, but also passages of utter despair and explosions of anger against heaven and hell. That lends it a great

amount of realism from a psychological point of view. It also makes it a real tour de force for any interpreter. The Pianto

della Maddalena is a masterpiece, and it gets a highly impressive and often moving performance by Nadine Balbeisi, who

brings out every nuance of the text.

No less impressive is Theodora Baka in the lament of Artemisia and in the role of Helen of Troy in Marazzoli’s lament.

Her voice isn't that much different from Ms Balbeisi’s, but has some darker streaks which are effectively used. The two

singers are an excellent match in the duet in the Lamento d'Elena invecchiata and in ‘Dovremo piangere la passione di

Nostro Signore’ - Let us weep for the passion of Our Lord. It was composed by Domenico Mazzocchi, another who

enjoyed the protection of the Barberini family. The piece consists of six stanzas, the first and last for two voices. The

programme ends with the closing episode from Luigi Rossi’s Oratorio per la Settimana Santa, an oratorio for Holy Week.

This is a lament by Mary which ends with the words: ‘Eyes, weep, yeah weep for evermore!’. Then follows a ‘madrigale

ultimo’ for the two voices which takes up the last line of Mary: ‘Weep, eyes, weep! Sorrows, torments, increase’.

An important aspect of this disc is the use of the various instruments. It is the first CD from Atalante, which Erin Headley

founded a couple of years ago with the explicit aim of performing and recording music written in Rome in the 17th

century. The name is derived from Atalante Migliorotti, friend and pupil of Leonardo da Vinci. More importantly, he was

the inventor of the lirone. Ms Headley is a latter-day pioneer of this instrument and was the first to commission the

building of a facsimile of the instrument which played such an important role in Italian music of the 17th century. With its

dark sound it was especially suited to laments, and this disc is all the proof that could be needed. Also interesting is the

frequent use of a harp in the basso continuo. This is particularly appropriate as both Rossi and Marazzoli played this

instrument. Lastly, in several items we hear a consort of viols. That is not something one associates with Italian music of

the 17th century, but such an ensemble was more widely used than is often thought. Whether consort players still

transcribed vocal pieces in the 17th century as they did in the 16th I am not sure. Two examples of such transcriptions are

included here: Spargete sospiri and Peccantem me quotidie, both by Luigi Rossi.

This is one of the best recordings I have heard all year. The repertoire is exciting, and so are the performances. It is thanks

to grants from the Arts & Humanities Research Council of Great Britain that this programme could be recorded. There is

more to come. I can hardly wait.

Johan van Veen Music Web International

…will surely come to be regarded as a something of a milestone.

The two discs under review by the group Atalante, which Erin Headley (who worked with Tragicomedia) formed

specifically to further explore this repertory, will surely come to be regarded as a something of a milestone in this history

of rediscovery and recuperation, including, as they do, music that has not only received little attention in the past but is

also mostly of the highest quality. Reliquie di Roma I: Lamentarium (Destino Classics/Nimbus Alliance NI6152, rec 2011,

67') contains a sequence of independent laments, nine to be precise, all except one having been transcribed from

manuscript sources (at times difficult to decipher), preserved in libraries in Paris, Rome and Oxford. The exception,

Domenico Mazzocchi’s Piangete occhi piangete, an extended and deeply moving meditation on the Passion of Christ, was

published in the Roman collection Musiche sacre e morali of 1640. This source situation is in itself highly indicative of the

social circumstances in which this repertory was largely composed and performed, namely for an elite local audience of

aristocrats, cardinals, distinguished foreign visitors, and intellectuals who gathered to hear them, as they also heard

sacred and secular operas and oratorios, in the grand palaces and churches of the city. As such it began life as a

specifically local phenomenon, a direct outcome of the atmosphere and priorities of Barberini Rome, with its

determination to advance the doctrines of the Catholic Reformation as well as the fortunes of the family. The Puritan poet

John Milton attended precisely such an occasion during his stay in Rome in 1646 when he heard a performance of the

opera Chi soffre speri, composed by Virglio Mazzocchi with intermedi by Marco Marazzoli, which had been commissioned

to inaugurate the new Barberini theatre.

The performances on this first disc are exquisite—a more powerful and persuasive advocacy for these pieces could hardly

be imagined. Kaleidoscopic shifts of colour, highlighted by movements in the instrumental parts carefully choreographed

to highlight textual meaning, articulate a constantly changing palette. This is not so much a question of accompaniment,

as might be conventionally described, but rather a fully integrated conversation between voices and instruments,

submerged in

an intensely alert and sensitive texture that is ever ready to acknowledge the significance of individual words and

phrases. The dedicated continuo ensemble is made up, somewhat unusually, of double harp, chitarrone, keyboards, viol

consort (a specifically Roman taste) and lirone, the viol-like bowed instrument whose large number of strings (14 or more)

and unique system of tuning not only allowed it to accommodate the unusual harmonic twists and inflections that are one

of the distinctive hallmarks of much of this music, but also offered the possibility of sustained chordal support. In

addition to its participation alongside the two soloists Nadine Balbeisi (soprano) and Theodora Baka (mezzo-soprano), the

instrumental group is also heard to full advantage in the three short instrumental pieces by Luigi Rossi, taken from vocal

originals (as was standard practice at the time), which punctuate the recording.

Iain Fenlon Early Music

The kaleidoscopic continuo expertly led here by the group’s director, Erin Headley, contribute enormously to the

success of this album.

In the Lamento d’Arianna (1608), Monteverdi was perhaps the first to set such a lengthy and tormented text to music. He in

turn was emulated by Bonini, Pari, Costa and Verso, whose settings were collected on an excellent CD for DHM by the

Consort of Musicke. In contrast to his colleagues, Cavalli punctuated his operas with striking laments; they function to

prolong the pain so as to give prominence to the pleasure.

The independent lament, demanding of performer and listener alike, is the genre explored in two new recordings: the

aggressive approach of Romina Basso (Naïve) contrasts with that of Atalante (Destino). Atalante’s CD is more subtle in

atmosphere and more original in content: their fascinating album shows that an entire programme of laments need not

entail monotony.

The only previously recorded work here is ‘Piangete occhi, piangete!’, which Atalante have extracted from an oratorio by

Luigi Rossi. Pain and despair are as welcome as the ‘wings that lift us to the throne of true glory’, for tears in counter-

Reformation Rome signalled relief rather than torment: suffering was pleasurable.

Theodora Baka’s mezzo-soprano is velvety and divinely smoky, and she brings those qualities effortlessly and eloquently

into play here. Marazzoli’s Lamento d’Artemisia casts the spell of a song without artifice: in quiet astonishment and infinite

tenderness, Artemisia laments the dead king, and in little more than ten minutes we succumb by degrees to her

unassuageable grief. More extended, at nearly twice the length, and equally effective is the lament of Mary Magdalene by

Luigi Rossi, in which the soprano Nadine Balbeisi’s transparent timbre and clear enunciation characterise the portrayal of

the holy penitent: throughout, she brings inspiration and generosity of feeling to her doleful, yearning recitation.

The two singers alternate in Marazzoli’s wonderful ‘Cadute erano al fine’ – as with most of this programme, a new

discovery – whose text combines two aspects of vanitas: the aging Helen of Troy meditates at once on her faded beauty

and on the irreparable destruction caused by war.

The kaleidoscopic continuo expertly led here by the group’s director, Erin Headley, contribute enormously to the success

of this album, and their entrancing sounds are complemented by the spectacle of selected scenes delivered in costume on

an accompanying DVD. Above all, the lasting impression is of plangent voices in compelling declamation over the

uniquely evocative, ghostly chords of Headley’s chosen instrument, the lirone.

Gaëtan Naulleau Diapason

If your head has ever been turned or your heart pierced by Monteverdi’s more famous laments, you’ll probably love

this.

This is an album of 17th-century laments. The subjects vary widely. Marco Marazzoli treats Helen of Troy and Artemisia,

Luigi Rossi deals with Mary Magdelene and the Blessed Virgin, and Marc’ Antonio Pasqualini and Domenico Mazzochi

focus on the birth and passion of Jesus. The musical responses range from the plaintive to the penetrating to the

momentarily explosive. Atalante is a new ensemble, directed by Erin Headley, which performs the music in staged

concerts, with period costumes and props. But the music-making has a kind of unassuming comprehensiveness that

communicates vividly without the need for visual stimulation. The two singers, soprano Nadine Balbeisi and mezzo

soprano Theodora Baka, have an affecting beauty of tone and blend perfectly. If your head has ever been turned or your

heart pierced by Monteverdi’s more famous laments, youll probably love this.

Michael Dervan Irish Times

I can’t believe that Lamentarium from Atalante director Erin Headley will not be in my top ten recordings of the

year.

Some really exquisite sounds from Atalante – the voices, perfect for this repertoire, were Nadine Balbeisi and Theodora

Baka and within the glorious instrumental texture you heard the harp of Siobhan Armstrong – and there are a couple of

chitarrone thrown in for good measure – quite irresistible – I can’t believe that Lamentarium from Atalante director Erin

Headley will not be in my top ten recordings of the year.

Tim Thurston RTE Lyric FM Ireland

Stirring renditions by soprano Nadine Balbeisi and mezzo Theodora Baka of little-performed works.

Erin Headley is the leading performer - probably the sole performer, in fact - on the lirone, a 17th century precursor of the

cello with between 9 and 14 strings, whose sound was said to move the emotions uncontrollably.

It’s matched here in the early-music ensemble Atalante with viols, harpsichord, chittarone and double-harp, in stirring

renditions by soprano Nadine Balbeisi and mezzo Theodora Baka of little-performed works by such as Luigi Rossi and

Marco Marazzoli. The laments - long and involved plaints of widows, Mary Magdalene and, in Marazzoli’s “Cadute

erano al fine”, an aged Helen Of Troy contemplating her decrepitude (”For you, Helen, Troy was vanquished?”), are

sensually melancholy, indulgences in heightened emotions. The lirone, meanwhile, is most effectively showcased in

Rossi's shorter bel canto pieces, where its complex, bittersweet warmth comes through most clearly.

Andy Gill The Independent

1 Passacaglia

Luigi Rossi

2 Elena invecchiata

Marco Marazzoli

3 Spargete sospiri

Luigi Rossi

4 Lamento d’Artemisia

Marco Marazzoli

5 Pianto della Maddalena

Luigi Rossi

6 Perché dolce Bambino

Marc’Antonio Pasqualini

7 Piangete occhi, piangete

Domenico Mazzocchi

8 Peccantum me quotidie

Luigi Rossi

9 Conclusion of Oratorio

Luigi Rossi

per la Settimana Santa

REVIEWS

ERIN HEADLEY - director

NADINE BALBEISI soprano

THEODORA BAKA mezzo-soprano

Paulina van Laarhoven and Annalisa Pappano - viola

da gamba

Nora Roll - viola da gamba and Erin Headley - viola

da gamba, lirone

Kristian Bezuidenhout - harpsichord

Siobhán Armstrong - arpa doppia

Elizabeth Kenny and Andrew Maginley – chitarrone

ATALANTE

Eternal lamenting,

extravagant

repenting, religious

ecstasy, passionate,

sensual, macabre

and erotic narratives

from 17th-century

Rome.

RELIQUIE DI ROMA I: Lamentarium

NI6152

Breathtaking performances of delicious music.

Marc Rochester Gramophone Magazine

OUTSTANDING Release April 2012 International

Record Review

Music of the highest invention and emotional sophistication

Andrew O'Connor International Record Review

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL

Recording Of The Year 2011

One of the best recordings I have heard all year.

Johan van Veen MusicWeb International

will surely come to be regarded as a something of a milestone.

Iain Fenlon Early Music

The kaleidoscopic continuo expertly led here by the group’s

director, Erin Headley, contribute enormously to the success

of this album.

Gaëtan Naulleau Diapason

If your head has ever been turned or your heart pierced by

Monteverdi’s more famous laments, you’ll probably love this.

Michael Dervan Irish Times

I can’t believe that Lamentarium from Atalante director

Erin Headley will not be in my top ten recordings of the

year.

Tim Thurston RTE Lyric FM Ireland

Stirring renditions by soprano Nadine Balbeisi and mezzo

Theodora Baka of little-performed works.

Andy Gill The Independent

the sound of excellence

the sound of excellence

the sound of excellence